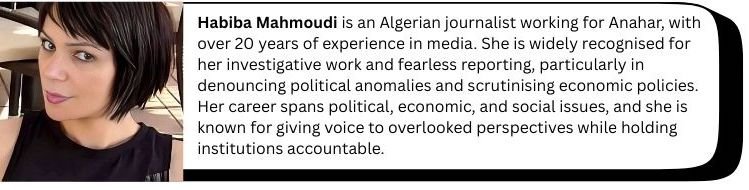

BY Habiba Mahmoudi

Algeria has reached a moment where pretending is no longer an option. For years, export diversification beyond oil and gas has been repeated like a comforting slogan, but slogans do not move containers, sign contracts, or build brands abroad. What exporters live every day is very different from what is said in conference rooms.

Algeria has reached a moment where pretending is no longer an option. For years, export diversification beyond oil and gas has been repeated like a comforting slogan, but slogans do not move containers, sign contracts, or build brands abroad. What exporters live every day is very different from what is said in conference rooms.

There is no doubt that the Algerian government wants to encourage exports outside hydrocarbons. Intentions exist. Declarations exist. Programmes exist. But intention without deep reform becomes noise. And exporters are tired of noise.

Algeria today is not the Algeria of yesterday. It is no longer the time of tchipa. That era, at least in my knowledge and experience, is finished. The problem is no longer corruption in its old visible form. The problem has become something far more dangerous: administrative paralysis dressed as procedure.

At the heart of this paralysis stands the MOH, l’administrateur, the anonymous decision-maker who does not sign, who delays, who asks for one more document, one more stamp, one more clarification. Not because the law requires it, but because power, in Algeria, is still exercised through obstruction. These administrators put hurdles in front of entrepreneurs not out of ideology, but habit. Control has replaced facilitation.

In one hand, you have Minister Rezigue, speaking about exports, ambition, numbers, and national pride. On the other hand, you have an administration that neutralises those ambitions at ground level. This contradiction is exhausting for entrepreneurs. A factory can be ready, quality can be there, prices can be competitive, but one missing authorisation or one delayed validation can kill a deal built over months.

I write this as Habiba Mahmoudi, with a background in journalism and reporting, someone who listens more than she speaks, and who has spent time with exporters, producers, and young entrepreneurs across sectors. What I see is not incompetence. What I see is frustration. A generation that knows how to produce, how to package, how to respect standards, how to communicate internationally — but is trapped inside a system that does not trust it.

Algeria’s youth is not waiting for miracles. They are ready to work. Production costs are low. Energy is affordable. Labour is competitive. The quality of production has improved visibly in agri-food, cosmetics, light manufacturing, and niche industries. The new educated generation understands that quality is not negotiable. They master it. They respect it. But quality alone does not export itself.

What Algeria lacks painfully is international marketing, storytelling, and professional PR. Algerian products are invisible abroad. There is no national export image, no emotional narrative, no coordinated presence in foreign markets. When Algerian companies go abroad, they go alone, unsupported, often unprepared, and rarely followed up. Exporting becomes an adventure, not a strategy.

And then there is the elephant in the room that policymakers avoid: hard currency.

As long as exporters cannot access foreign currency at a realistic rate, the system will continue to push them towards informal solutions. This is not ideology. It is survival. When the Algerian dinar has one value at the bank and another on the black market, exporters will calculate accordingly. They are not criminals. They are economic actors responding to distortion.

The real value of the dinar is not what is written on paper. It is what the market says it is. This gap between official and parallel rates poisons the export ecosystem. It encourages under-invoicing, informal channels, and mistrust between the state and entrepreneurs. If Algeria truly wants to stop informal exporting practices, the solution is not repression. It is alignment. The dinar’s value must reflect reality, or at least approach it closely enough to remove the incentive for parallel behaviour.

Exporters need clarity. They need predictability. They need to know that when they export, they will be able to repatriate currency, pay suppliers, reinvest, and grow without navigating grey zones. Until then, speeches about export patriotism will remain disconnected from economic reality.

Another painful truth must be said: Algerian exports are not established in foreign markets. Presence is weak, fragmented, and mostly limited to diaspora channels, especially in France. Outside of that, Algerian brands are absent from mainstream retail shelves. This is not because products are bad. It is because market entry requires time, consistency, volume, logistics, and above all, institutional backing.

Entrepreneurs cannot do this alone. No country ever succeeded in exports by leaving its producers isolated.

Bureaucracy, again, sits at the centre of the problem. Too many steps. Too many approvals. Too many interpretations of the same rule. Exporting should be encouraged, not treated as a suspicious activity. Today, exporting in Algeria still feels like asking permission to succeed.

The tragedy is that the potential is real. Tangible. Immediate. Algeria could export far more if the system trusted its own people. If administrators were evaluated on facilitation, not blockage. If ministries spoke to each other. If marketing was taken seriously. If the dinar reflected reality.

Diversifying exports outside oil and gas is not a luxury. It is an obligation. Economically, socially, and politically. The youth already knows this. The entrepreneurs already know this. The question is whether the system is ready to let go of control and embrace confidence.

Because the world will not wait. And potential, when ignored too long, turns into resentment.